Volvo ÖV4

The very first Volvo

In the Roaring Twenties, people are living life to the fullest. It is a decade when automotive manufacturing gets rolling around the world. And in Sweden, the race is on to serial produce a car. Volvo wins.

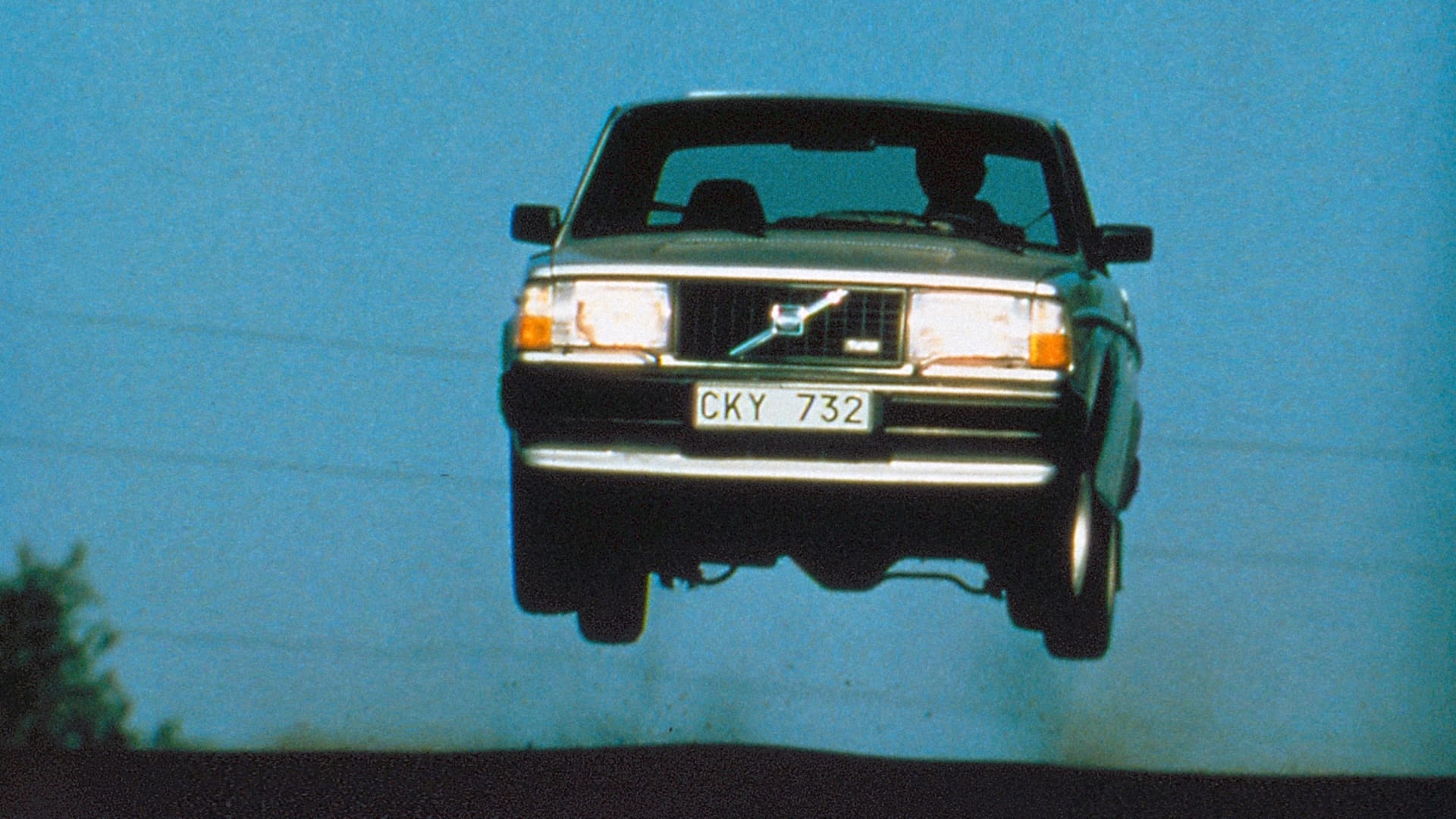

The premiere of the ÖV4 falls flat; a rear axle gear has been installed incorrectly and the car can only drive in reverse in its first test drive from the factory. The mistake is immediately fixed and from that day, Volvo moves forward.

Every story has a beginning

It could be a meeting at a café. A crayfish party. Perhaps a job in England. Or when a car is reversed out of a factory on April 14, 1927.

That car is named ÖV4, Open Car 4 cylinders, and with it, we let the story of Volvo begin. It's an exciting time. World War I is over, the Spanish flu has subsided, the Roaring Twenties begin, and both the economy and culture flourish. New dances are created, like the foxtrot and the Charleston. The new music, jazz, is heard everywhere.

Now, cars and motoring are also rapidly growing, in pace with better purchasing power and people's growing appetite for travel. With increased demand, it's time to start car manufacturing in Sweden too. But competitors are already far ahead, especially American manufacturers, accounting for 90% of imports to Sweden and also assembling cars here. In the 1920s, the T-Ford represents over half of the Swedish car fleet.

Attempts to start car manufacturing are made early on by Scania, later by Thulinverken and Tidaholm, but they quickly give up on passenger cars. In 1925, discussions about a Swedish car company continue and are reported in Teknisk Tidskrift:

We have within the country the conditions and possibilities required to start Swedish automobile manufacturing on a larger scale than before. What we lack is the man who wants to tackle the task and who has the ability to gather good forces around him.

But that man exists – in Gothenburg. As sales manager at SKF, Assar Gabrielsson has already tried to convince management to invest in Swedish passenger car manufacturing, without success. Another man is needed: Gustaf Larson. When Assar Gabrielsson encounters him at a spontaneous crayfish party, Larson is tasked with designing a car. This happens via an oral agreement. No formal contracts are written.

Gustaf Larson has worked at both SKF and White & Poppe in the UK, where a certain William Morris also gets help to design an engine for his car project – which becomes the car brand Morris. William Morris' business idea is to buy components from independent suppliers and then assemble them in his own factory, just as Volvo will do 15 years later, a method then called "making cars the Volvo way."

When Gustaf Larson is given the task of designing a car, he is employed as a technical manager at Galco, so the work must be done in the evenings at home at Rådmansgatan 59, where the nursery is eventually turned into a drafting office. He works without compensation, which will be paid out "only if mass production is started by January 1928." Assar Gabrielsson handles the finances, and he calculates the new car's costs as early as 1924. He estimates an investment of 1.6 million kronor and manufacturing 4,000 cars per year, which in wages, materials, and other expenses would amount to 5.6 million kronor.

The materials in the car amount to 600 kronor, and the car's cost price is 1,400 kronor. Assar Gabrielsson later states the intended price to be 2,000-3,000 kronor, but ultimately it ends up at 4,800 kronor. In June 1925, the drawings for the car's chassis are completed. Gustaf Larson seeks help from Jan G. Smith, who designs the basic mechanics, such as the chassis frame and gearbox. The engine is designed by Gustaf Larson, drawing on his experiences from his time at White & Poppe, as well as with knowledge of how American manufacturers' engines are made.

Ten cars

Assar Gabrielsson and Gustaf Larson decide to build ten cars in a trial series, which can be shown to potential investors. On October 8, 1925, ten engines are ordered from Pentaverken in Skövde. A few months later, the chassis frames are ordered from Bofors. Assar Gabrielsson personally guarantees the orders with 150,000 kronor, earned from commissions at SKF.

The car, named "Larson" in all documents, also needs a body. It's already decided that Svenska Stålpressnings AB in Olofström will handle production – but who will design it? It turns out that Gabrielsson and Larson have a mutual and very car-interested acquaintance: the well-known landscape painter Helmer MasOlle. He has already drawn and had a body built for his car from the French brand Voisin. MasOlle is also the brother-in-law of an SKF director, which makes him an easy choice.

He designs both an open and a covered body, but much later, he doesn't want to acknowledge the covered car, PV4, which goes into production. It's considered ugly and gets the name "Orrekojan" (the birdwatching hut) – and doesn't look like the car MasOlle designed. Many features in the bodies can also be seen in cars from Voisin. MasOlle also designs the classic Volvo emblem: a slanted diagonal and the symbol for iron, also called the Mars symbol. It's still on the front of all Volvo vehicles.

The story of their names

When the drawings are completed, the coachbuilder Adolf Freyschuss in Stockholm is commissioned to build the ten bodies. He is the most popular but also the most expensive coachbuilder, and choosing Freyschuss is a sign that Gabrielsson and Larson don't want to go for a budget model. Freyschuss performs a credit check to ensure that the two young men will be able to pay for the large order.

The ten prototypes are given different names and colours to keep track of them. One is named Jakob because it was completed on July 25, Jakob's name-day. Emil is ready at Emil’s name-day in November. The Mermaid is blue-green.

In July 1926, the first prototype car is completed, and Larson and Gabrielsson drive to Gothenburg to present it to SKF's management. They try to sell the project by saying that the car will have higher quality than Fords, but at a lower price. A month later, SKF has a board meeting in Hofors and decides to subscribe for a share capital of 200,000 kronor in the new company AB Volvo. The name has been registered by SKF since 1915 and is intended for ball bearings. The agreement includes a loan of one million kronor, and Assar Gabrielsson is appointed CEO from January 1, 1927.

SKF also provides factory premises on Hisingen for Volvo. The entire company moves there from Stockholm, which happens in three of the finished, open prototypes. Assar Gabrielsson brings his wife Tessan in his car, Gustaf Larson drives with the engineer Gotthard Hallgren, and the third car is driven by engineers Eric Carlberg and Henry Westerberg, who account for much of the design work and are considered Volvo's first employees.

The journey to Gothenburg

The journey to Gothenburg is eventful. In Malmslätt in Östergötland, there is an overtaking of a truck, and one of the test cars meets a T-Ford, which is scraped clean of fenders and running boards. Only the hubcaps are damaged on the Volvo. So, Swedish steel proves to be tough, but Assar Gabrielsson is forced to reach a financial settlement with the driver of the T-Ford.

When darkness falls, it turns out that only Gabrielsson's car has functioning lights and a horn. They try to drive in a convoy, but in the dense darkness, it's sometimes hard to see where the car in front is going. One car veers off the road and ends up in a lake. After joint efforts to get it back on the road, the journey continues.

As the caravan approaches Gothenburg, new trouble arise. The roads are filled with people heading home after a dance evening. They stagger across the road, don't see the cars without lights, and the drivers have to warn by revving their engines. The police stop the caravan; the drivers must explain themselves before they eventually continue their trip. As a final touch to the whole journey, one of the cars ends up on a tram track in Gothenburg. It has to be pushed off by hand, not exactly a grand entrance into the city that will become the new car manufacturer's home.

In August 1926, a press release is sent out, probably from SKF, about the new Swedish car. Almost all newspapers publish the pictures; some reporters even get to test drive it. But the real tough test is performed by Ivar Örnberg, a Swedish engineer working in the USA, who is on a temporary visit to Sweden. He will later return to Sweden and Volvo and independently design PV36, Carioca, but now he takes a few colleagues and three ÖV4 prototypes – and returns with harsh criticism.

Örnberg believes the car should have a six-cylinder engine, the body's design provides insufficient space, the foot brake isn't effective enough, the cardan shaft whines, the engine vibrates, and the frame is too weak. Volvo's management responds that they intend to first build 1,000 cars with a four-cylinder engine but are already working on a six-cylinder. The vibrations come from poorly balanced crankshafts and flywheels, so the crankshaft is given increased dimensions.

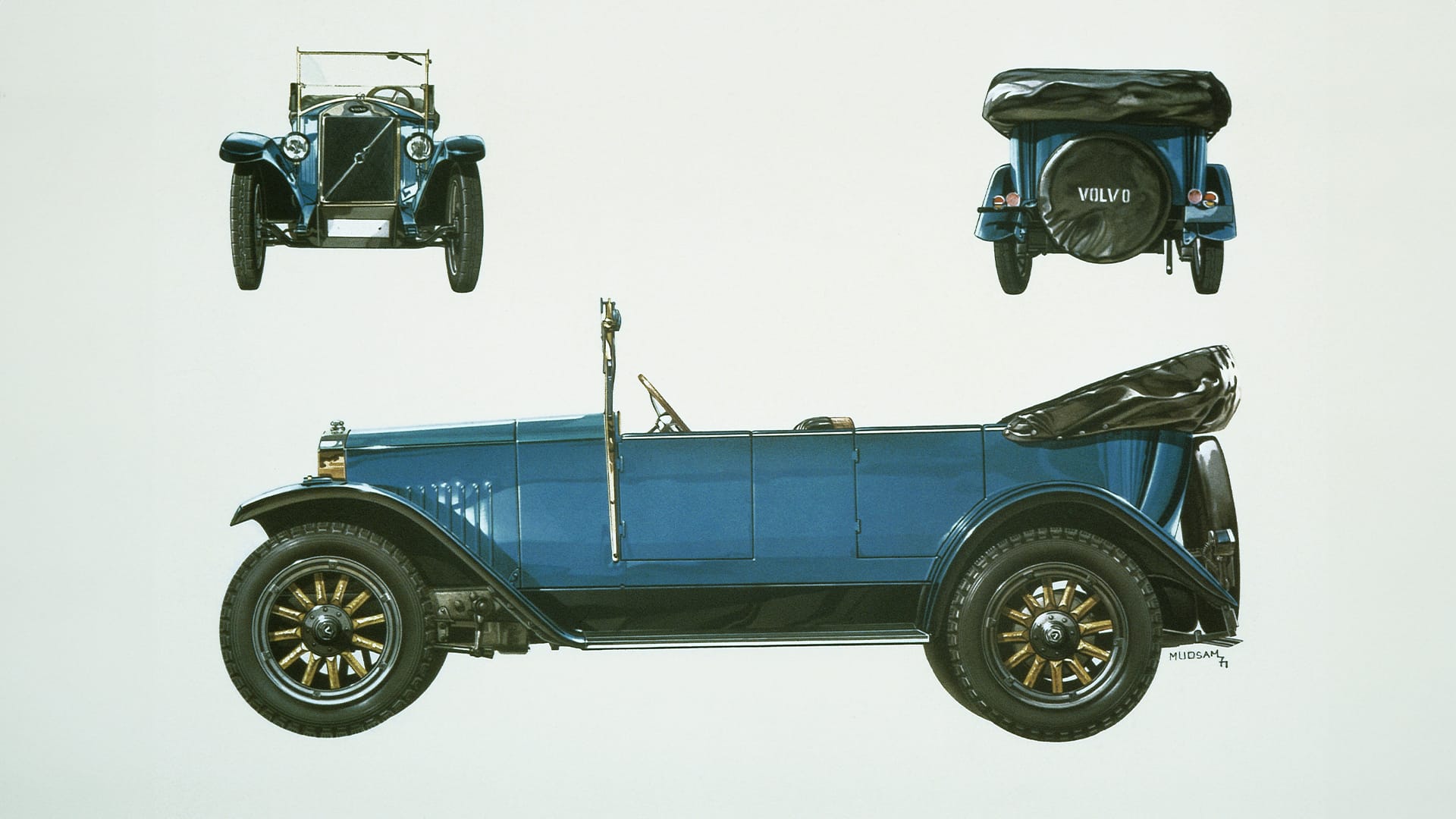

After the adjustments, the ÖV4 is ready for serial production. The car is built on a chassis frame, where front wheels, rear axle, engine, gearbox, and cardan shaft are suspended. The brakes are mechanical and only act on the rear wheels. It has four doors and is sheet-metal clad on a wooden frame of ash and red beech. The side windows are made of celluloid. The first cars can only be obtained with a dark blue body and black fenders. The interior has five seats with leather upholstery and a dashboard in brown-polished red beech, equipped with light switch, parking light contact, oil pressure gauge, and fuel gauge and speedometer.

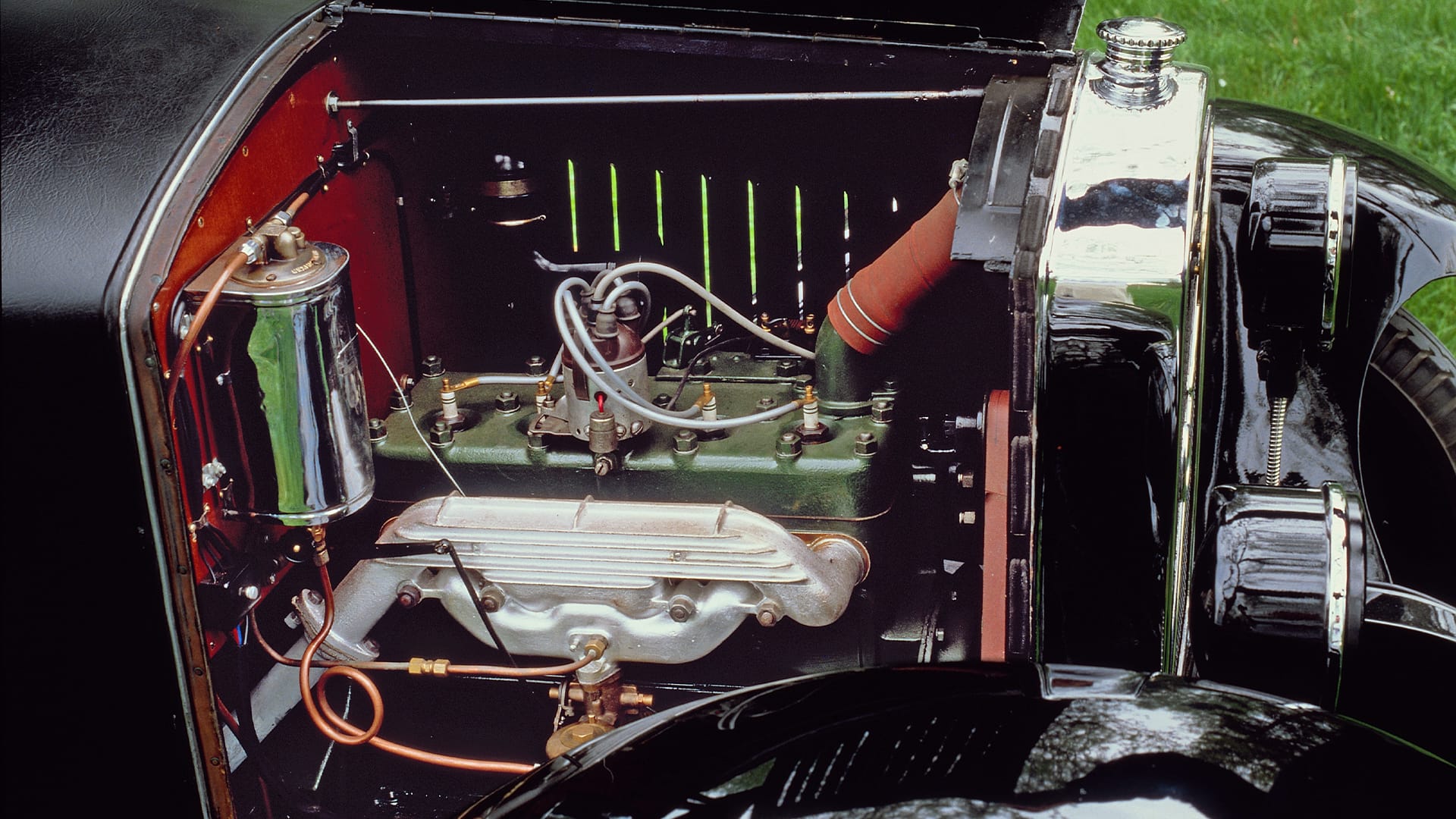

The engine

The engine is a four-cylinder side valve of two liters, providing 28 hp. The power is transmitted via a three-speed, unsynchronized gearbox. The top speed is 90 km/h, but Volvo advises to keep it to 60 km/h. Just after 10 o'clock in the morning on Maundy Thursday, April 14, 1927, the first serially produced car is driven out of the factory gate. Sales manager Hilmer Johansson sits behind the wheel and is thus forced to back out the car, due to a wrongly mounted gear in the rear axle. Gustaf Larson witnesses the incident and says to the foreman Fingal, who is in charge of assembly: "Now Fingal has harnessed behind the horse's rear!” This somewhat anticlimactic premiere later takes on mythical proportions, something that irritates Assar Gabrielsson and Gustaf Larson many years later. In fact, it takes ten minutes to fix the problem, and then the car runs as it should.

Manufacturing and quality

Sixty employees work on manufacturing the new car, and they expect to make five cars per day. The price at introduction is 4,800 kronor. The covered variant PV4 comes a few months later. The wooden frame is covered with pegamoid, a kind of artificial leather, because the wooden frame cannot support a sheet-metal body. The price for PV4 is 1,000 kronor higher, and the intention is to build 500 units of each model during the first year.

But customers are skeptical and only 201 units of the ÖV4 are sold in the first year. Four more ÖV4s are built, but it's not until 1930 that the last one is sold. Volvo doesn't have a flying start as a car manufacturer. The price deters, and customers would rather have six-cylinder engines, besides, open cars are not suitable for the Swedish climate. At this time, in the USA, 80% of cars are covered, so the strategic choice of the Volvo founders is undoubtedly surprising.

The quality is also poor. At high speeds, the car shakes, and the wooden frame creaks. To counteract this, customers hang wet rags on the wheels so that the frame and wheel rims will swell. Nor is the pegamoid on PV4 entirely successful. The first buyer of an ÖV4 is either manager Gunnar Håkansson in Sandared outside Borås – or more likely the dealer Ernst Grauers in Stockholm, whose contract bears an earlier date. At that point, the story of Volvo's first car remains somewhat unclear.