Volvo 850 BTCC

The fastest estate in the world

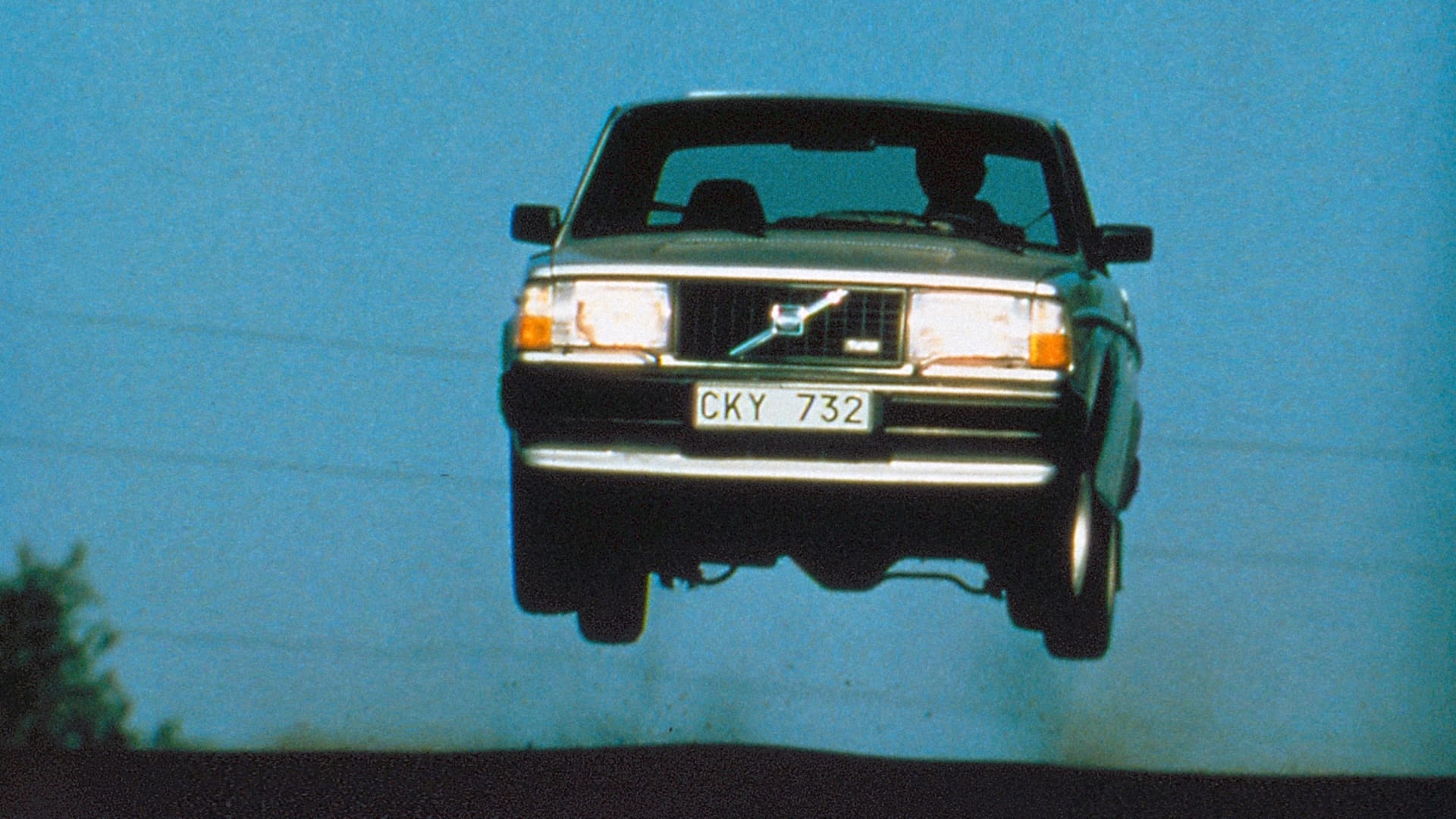

A family wagon on a race track? It sounds absurd, but when two Volvo 850 estates roll up to the starting line for the 1994 BTCC race at Thruxton in southern England, the impossible becomes reality. This marks Volvo’s big return to motorsport after an eight-year break, and the buzz is huge

Behind the wheel of one car is 26-year-old Swede Rickard Rydell, who, when he signs his contract, has no idea he’ll be racing a family wagon. To tease the competition even more, a stuffed collie sits in the boot during the parade lap before a race. The car boasts a 280-horsepower engine, weighs just 950 kilos, and is the first BTCC car fitted with a catalytic converter. The following year, a new BTCC regulation effectively prevents estate cars from competing.

The “Back on Track” project

The seed for Volvo’s entry into the BTCC is planted by the company’s British importer. They push strongly for modernising and strengthening the brand, aiming to shake off the “old man in a hat” image that is seen as harming sales. This message reaches key figures in Volvo’s leadership, including Martin Rybeck, then head of Development, who secretly begins optimising the 850 model. An internal project called “Back on Track” is born.

An estate on the track? The unexpected racing move

Volvo had stepped away from international circuit racing in 1986, but internally, many now feel it’s time for a comeback. A small engineering firm, S.A.M. Steffansson Automotive AB in Kungälv, north of Gothenburg, is tasked with creating a racing prototype of the 850. The timeline is extremely tight, and when the team visits Volvo in Gothenburg, the quickest solution is to grab an estate body. This seemingly random choice sparks curiosity in Martin Rybeck, who decides to put the estate through wind tunnel testing. Surprisingly, the results show that the estate is no less aerodynamic than the saloon – in fact, it might even have a slight advantage.

From a marketing perspective, it seems like a stroke of genius: Volvo’s reputation as a maker of estate cars is already rock-solid – so why not spice it up with some racing in the BTCC (British Touring Car Championship)? Volvo reaches out to the British firm TWR, owned and run by the dynamic Scotsman Tom Walkinshaw. TWR brings extensive experience in racing, with a strong track record in both Formula 1 and touring car competitions.

“Real men don’t drive Volvo”

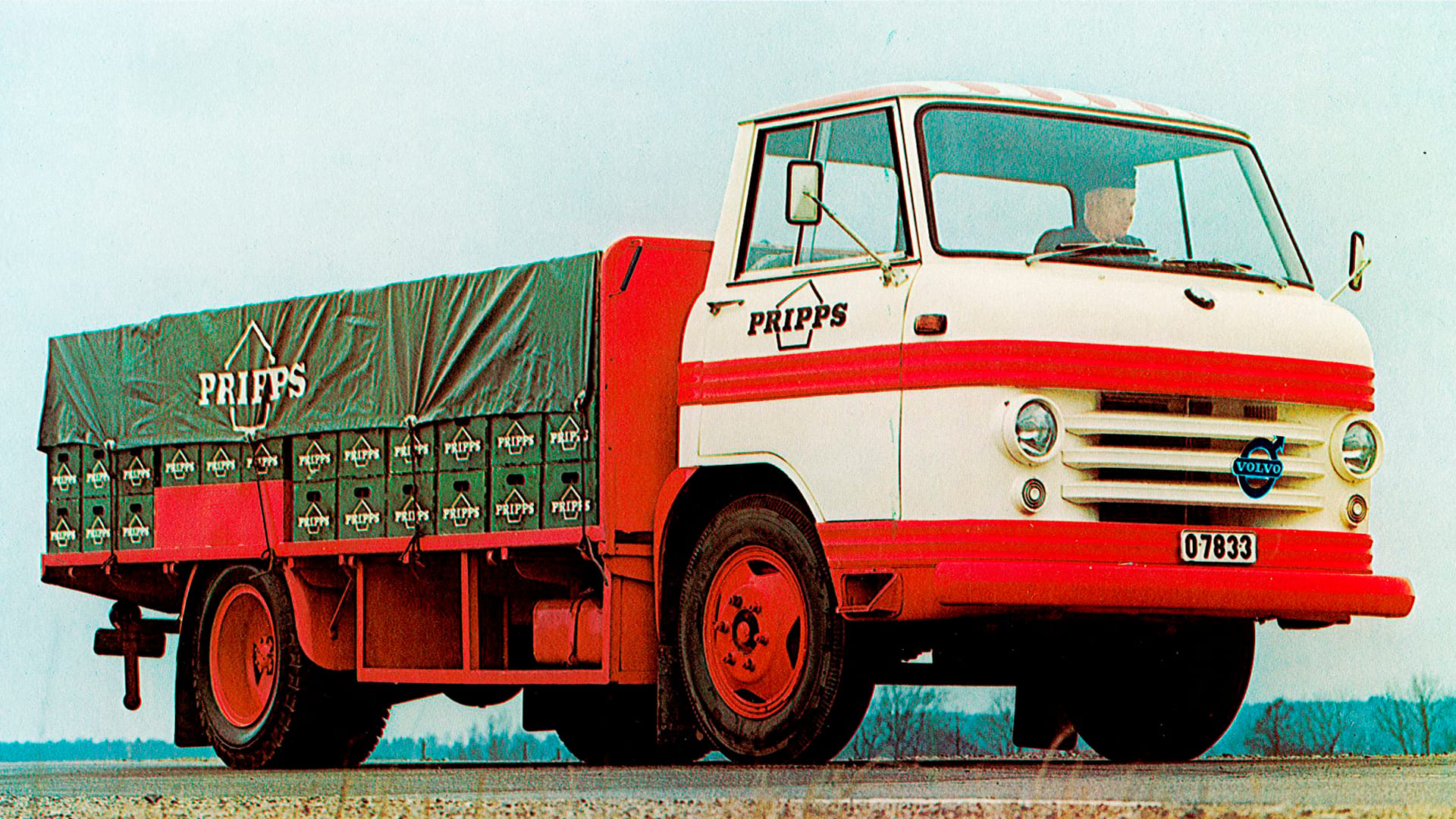

It’s a slightly ironic twist that Tom Walkinshaw, during the 1980s, ran racing teams for both Jaguar and Rover in the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC), directly competing with Volvo. Volvo famously won the championship in 1985 with the 240 Turbo, but not without tension. Walkinshaw’s cars even sported a cheeky sticker on the rear window that read: “Real men don't drive Volvo.”

Adding to the irony, it was protests from Walkinshaw himself that led to Volvo leaving motorsport in 1986. He accused Volvo of using lead-free, 99-octane petrol during a race at Anderstorp in Sweden, allegedly breaking the rules. He also claimed their cars at the Zeltweg race in Austria had fuel tanks of the wrong size. The FIA (Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile) investigated and annulled two of Volvo’s wins, which cost them the championship and resulted in their withdrawal from circuit racing.

Walkinshaw hits the breaks, changes his mind and races with Volvo

So when Tom Walkinshaw arrives at Volvo in Gothenburg eight years later for the “Back on Track” project, he’s met with frosty reactions from several employees. Walkinshaw’s initial response to the proposed car, the 850 estate, isn’t exactly enthusiastic either: “It’s a truck!”

He’s given the chance to test drive the car at Volvo’s proving ground in Hällered and just about manages to change his opinion when the bonnet suddenly flies up and covers the windscreen. Someone had forgotten to secure the pins that keep it in place. Despite the mishap, the partnership moves forward.

It’s a truck!

A family estate on the surface, a racer underneath

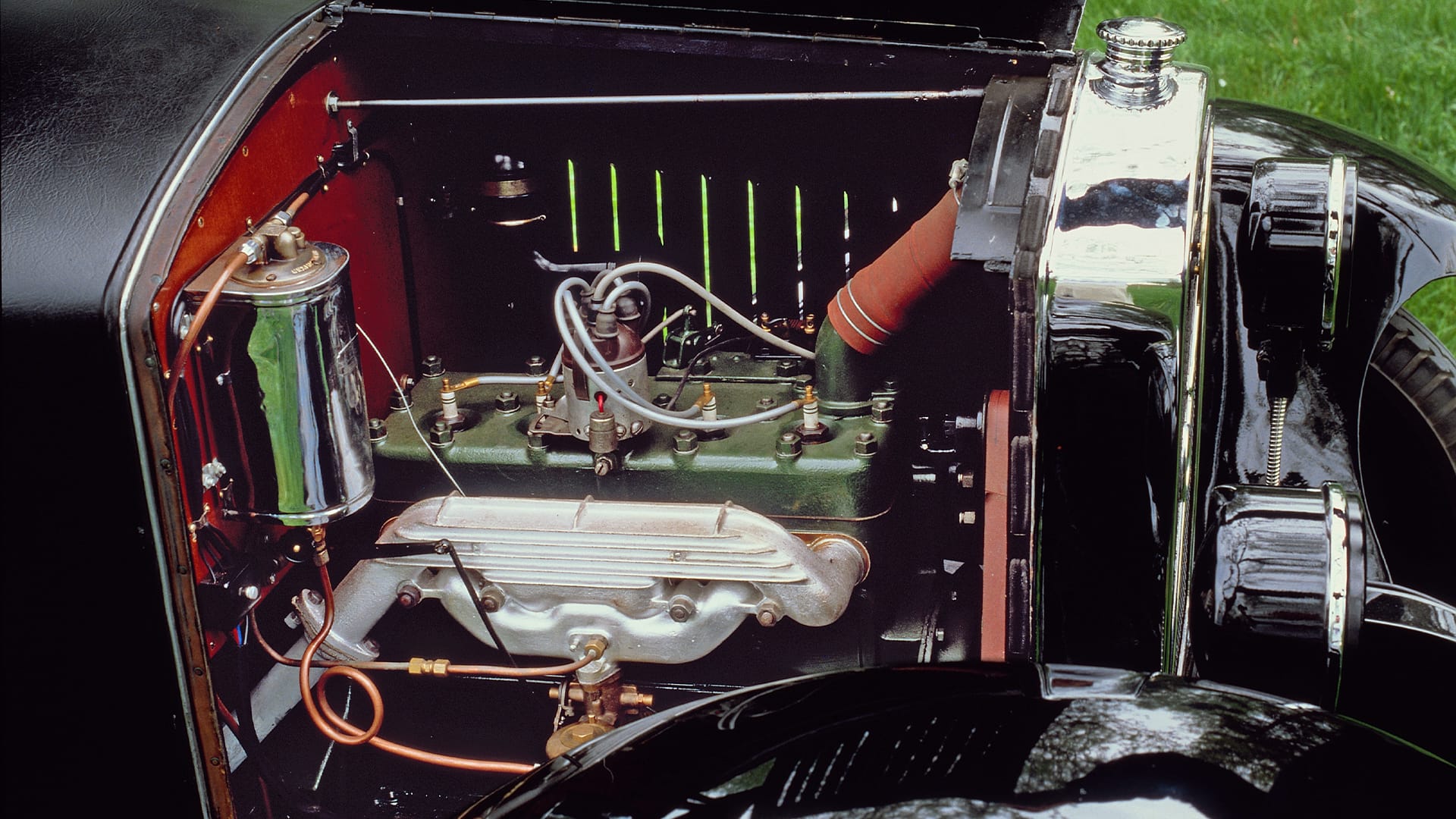

One of Tom Walkinshaw’s greatest strengths is his creative interpretation of motorsport rules. His guiding principle? Anything not explicitly forbidden is fair game. The BTCC has strict regulations aimed at keeping manufacturers’ costs in check: engine capacity must not exceed two litres, revs are capped at 8,500, turbos are banned, the minimum weight is 950 kilos, and the bodywork must remain standard. In practice, though, Volvo’s BTCC car will have very little in common with the family-friendly 850.

The car is designed by TWR’s Richard Owen, the same man behind Jaguar’s iconic supercar, the XJ220. Its body is reinforced with a welded steel cage to boost crash safety and rigidity. TWR’s engineers start with the five-cylinder, 2.3-litre turbocharged engine producing 225 hp. A lot of effort goes into reworking the cylinder head to accommodate larger camshafts and a new valve angle. Conveniently, there’s no explicit rule forbidding such modifications.

While official costs are undisclosed, reliable sources suggest that the cylinder head alone for the BTCC car costs around SEK 150,000 – compared to just SEK 2,000 for the standard version.

Walkinshaw and Bamber: the art of pushing limits without breaking rules

These tweaks give the engine a boost to 290 hp – 30% more than the standard version. Not surprisingly, the changes raise eyebrows among competitors, but Charlie Bamber, who worked at TWR and oversaw Volvo’s racing engines, later said in an interview: “It was queried at every race, and time and again, proved to be within the regulations. It is a production head – there is no way it was anything else.”

Other changes were made too. The gearbox was swapped for a six-speed sequential X-Trac, which allowed the engine to be lowered and moved behind the front axle. This also meant the driver’s seat could be shifted further back towards the middle of the car for better balance. Of course, that called for some creative engineering, with both the steering column and pedals needing to be extended. The 850’s standard Delta-link rear axle is fine-tuned, and the car is equipped with Öhlins dampers all around. Brakes from Brembo are fitted within the 18-inch wheels. Volvo becomes the first team to use catalytic converters on its cars, a feature that later becomes mandatory in the regulations.

Longest, largest, and impossible to ignore

With the racing version of the Volvo 850 ready for the BTCC grid, two drivers are signed: Dutchman Jan Lammers, boasting 20 years of experience in F1, Le Mans, and IndyCar, and 26-year-old Swede Rickard Rydell. Rydell, who understandably isn’t as seasoned but has an impressive background, winning Swedish go-kart championships in 1985 and 1986, and driving Formula 3 for Swedish, British, and Japanese teams.

Even for Rydell, the estate concept comes as a surprise: “When I signed with Volvo and TWR around Christmas 1993, I didn’t know about the estate plans. If I had, I probably would’ve hesitated,” he later admits in an interview. But he quickly realises the estate has its perks: “Aerodynamically, it was slightly better than the saloon. What really made the difference, though, was the attention the estate would attract.” And attract attention it does. The 850 estate is by far the largest car on the grid – and, of course, the only estate.

A PR success

From the start, competitors mock Volvo for entering what they call a "truck," but Volvo has the perfect comeback. During the parade lap before one of the races, they place a stuffed collie in the boot of one of the cars. The stunt gets plenty of attention, the PR move works like a charm, and Volvo generates more headlines than any other competitor, giving their reputation as an estate car manufacturer a solid boost.

Things move so quickly that Rydell and Lammers don’t even get a proper chance to test the cars before the season opener at Thruxton on 4 April 1994 – apart from driving a few hundred metres on the driveway outside TWR’s development centre.

As for the actual racing, it’s far from a roaring success. When the season wraps up at Donington Park on 21 September 1994, after 21 races, Rickard Rydell finishes 14th overall, with Jan Lammers just behind in 15th. Volvo places eighth in the constructors’ championship.

The comeback of Rydell and Volvo

There would be no more racing with the 850 estate in the BTCC. During the season, Alfa Romeo conducts various aerodynamic tests and pushes through a rule change allowing additional spoilers and wings. This effectively spells the end for the estate as a race car.

For the 1995 season, Volvo switches to the 850 saloon, and by 1997, they move on to the new S40. That year, Rickard Rydell secures a fourth-place finish, and the following year, he takes the ultimate prize, winning the entire BTCC championship.